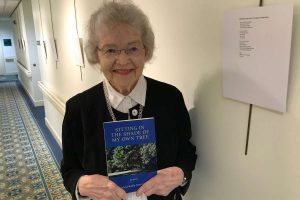

“Marylou Kelly Streznewski is the poet laureate of Beverwyck, an independent senior living community.

At 87, she is an advertisement for commitment to the writing craft, resilience and having a very thick skin.

Her first book, published when she was 65, was rejected 72 times before it found a publisher.

On Saturday, Streznewski submitted a short story to the literary journal Sequestrum after it had been turned down more than once by other publications.

“Rejection is what you live with as a writer,” she said. “I keep all my rejections in a folder and it gets fatter and fatter. My writer friends and I joke that we’re going to wallpaper a bathroom with rejection letters one day.”

I met Streznewski when I spoke at the women’s luncheon on Sept. 21 at Beverwyck. We talked about her writing career and she invited me to see a display of her poetry in an exhibit space. She printed and mounted on foam board a dozen poems and included copies of her published work, which also includes fiction, non-fiction and journalism.

I was drawn to a stanza in her poem “Pandemic Morning,” which hung in the hallway. “Maple buds sprinkle rubies in the flower beds/Daffodils turn their trusting faces toward the light.”

“I think she is a marvelous wordsmith,” said Evelyn Bernstein, 82, an organizer of the women’s luncheon speaker series and editor of a community newsletter, Beverwyck Bulletin. “She has beautiful descriptions. She’s a marvelous addition to Beverwyck and our vibrant community.”

Streznewski moved to Beverwyck in March after her husband of 63 years, Thomas Streznewski, an electronics engineer, died in August 2020 at 90. They lived for decades in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, where Streznewski taught high school English for 28 years.

Streznewski “started fooling around with poetry a little bit” while earning a master’s degree in English from The College of New Jersey and admired the powerful poems of W.H. Auden and Richard Wilbur.

She raised four children and joined a community writing group at Bucks County Community College led by Christopher Bursk, a noted poet and activist who died in June at 78. Bursk became her mentor. She dedicated her new poetry volume, “Sitting in the Shade of My Own Tree” to her father and to Bursk “who inspired me to keep trying to make the words into art.”

Streznewski began writing feature stories for The Intelligencer in Doylestown, Penn. She served as poetry editor of the Bucks County Writer, a local journal. Her high school English classes, which spanned from failing students to college-bound academic achievers, gave her the idea for her first published book.

After 72 rejections, John Wiley & Sons published “Gifted Grownups: The Mixed Blessing of Extraordinary Potential” in 1999 to solid reviews and strong sales. She interviewed 100 intellectually gifted men and women between the ages of 18 and 90. One surprising finding from Streznewski’s research was this: Gifted adults comprise as much as 2

0 percent of prisoners in the U.S.

“The book is still in print and I am still collecting small royalty checks,” Streznewski said. The book was also translated into Chinese and was published in Taiwan. More than 100 libraries worldwide acquired the book and it is used as a textbook in several graduate courses.

In 2006, after recovering from open-heart surgery, Streznewski published “Heart Rending – Heart Mending,” a research-based memoir that described her use of integrative medicine. She advocates the healing qualities of meditation, acupuncture and yoga – which she continues to practice in a class at Beverwyck.

In 2015, Streznewski published an anti-war poetry collection, “Dying with Robert Mitchum,” which debunks the myth perpetuated by the Hollywood actor’s persona of dying gallantly in romanticized wars. She writes in one poem: “If this is Armageddon, if this is how we end/I would want them to know, those who dig/in our ruins, who we were, how we lived.”

While Streznewski likes to extol the beauty of nature, she also turns a sardonic eye to social constructs in her poem titled “Minimum Security Facility – Suburban.”

She writes: “I was on my honor/not to flee,/but sometimes/when all my lost music/sang across the blazing death/of an autumn afternoon,/here,/where no one watches,/I danced.”

“I warmed to her verses because her poetry is very evocative,” said Estelle Yarinsky, 89, who purchased a book of Streznewski’s poetry. Yarinsky is a textile artist who previously displayed in the gallery a series of self-portraits made during the pandemic lockdown.

Both women attend a Beverwyck poetry group, led by Roger Kessel, where residents read, analyze and discuss published poems they select.

Some of Streznewski’s poems, as well as those discussed by the poetry group, confront issues around aging.

“There’s kind of a stigma around aging,” Bernstein said. “Before I moved here, some of my friends said why would you want to live with a bunch of old people. I said because I’m old.”

Yarinsky noted that she forced herself to look carefully in the mirror every day during the COVID lockdown to sketch a self-portrait. “Seeing the aging process up-close can be shocking,” she said.

Streznewski continues to submit to publishers her novel, “Watching Anna,” which centers on a 90-year-old woman quarreling with family members. Anna wants to be allowed to age in place instead of moving into a nursing home, where her children feel she would be safer and more comfortable.

“I get a lot of rejection letters that praise my dialogue, but say the novel is not what they’re looking for,” Streznewski said. “I get it. What’s hot in publishing now is underrepresented populations. I want to say, ‘Hey, how about senior citizens? Aren’t we underrepresented, too?’ ”

Paul Grondahl is director of the New York State Writers Institute at the University at Albany and a former Times Union reporter. He can be reached at grondahlpaul@gmail.com